Trevett McCandliss, Creative Director at Earnshaw’s & Footwear Plus

/SPD: What year?

Trevett McCandliss: 1989-90

SPD: What were you up to?

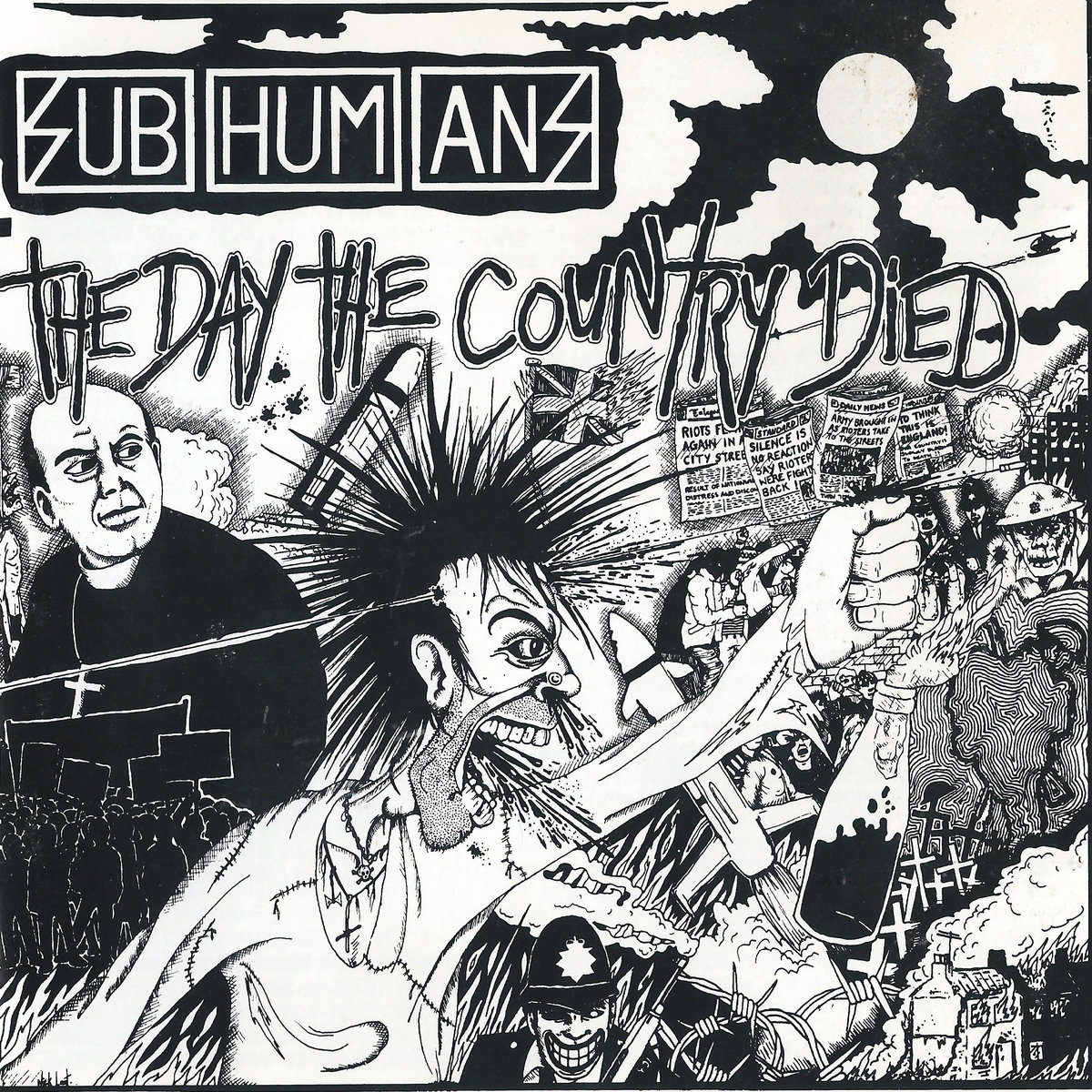

TM: I was discovering punk rock and learning to play the bass. The Germs, Subhumans, Misfits and Dead Kennedys were my favorite bands at the time. My friend’s sister’s boyfriend indoctrinated me into the mystries of loud guitar music in their suburban basement. He would sit with me for hours showing me the proper way to set up a Fender Twin, how to restring a guitar and instructing me as to why high action was better. The following year (in ninth grade) I had my own band that played one gig at our high school talent show. I had painted punk rock logos on my black army jacket and was sporting a mohawk that my friend gave me over the summer. (My mom was extremely displeased with my choice of haircut.)

SPD: What magazine?

TM: Maximum Rocknroll, which started its print run in 1982 as a booklet inside the Dead Kennedys double-LP “Not So Quiet on the Western Front”, released by Alternative Tentacles. The Maximum Rocknroll staff was all volunteer (still is), espoused radical politics, and covered the regional punk rock scenes around America and the world. It was pretty much cut-and-paste collage, black-and-white and made on a copier. It perfectly encapsulated the cheap, DIY, no frills, no budget, all-volunteer idealism that punk music represented. Being associated with this world, however tangentially, held the promise of personal transformation through creativity.

SPD: What was it that so enthralled you?

TM: The visual language of Maximum Rocknroll was expressive and direct with a purity and brutality that appealed to my aesthetic sense at the time. The same visual ideas seen on the covers of my favorite punk records—Bedtime for Democracy, Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death, This Is Boston, Not LA, The Feeding of the 5000, etc.—were the same ones being used in their editorial design. I could also easily grasp how it was made. Everything was black-and-white, mostly hand-done, typed on a typewriter (or what I thought was a typewriter) and collaged. The world it opened to me was exciting and exotic—teenagers in bands living together in a cheap house, skateboarding and making records. It seemed like an amazing way to live. Maximum Rocknroll also formed the visual template for a poetry magazine, Fever Dream, that my friend and I created on a copier. He was the editor-in-chief and I was the art director—not that I knew what an art director was back then.

Collecting punk records became a big pastime for me, and Maximum Rocknroll was the only real link to the world that those records came from. There were no band websites or blogs back then. MTV didn’t feature them either. These bands were too cool and controversial for the mainstream, which is just what I loved. The only way to get punk records was to send away for them in the mail or buy them from Newbury Comics in Boston. For a teen from a sleepy New Hampshire town, Boston was the big city. It was always very exciting to visit and check things out. I would peruse other indie magazines, like Transworld Skateboarding, Thrasher and Spin. They were all awesome, but they weren’t made with a language that spoke as directly to me as Maximum Rocknroll. And while those magazines featured beautifully lit skateboard sequences, celebrity portraits and professional illustrations, none of that was something I could create or commission. Give me grainy black-and-white photos that have been photocopied a hundred times any day! Maximum Rocknroll represented a world filled with passionate, creative people living the art life, and I wanted to be a part of it.

SPD: Do you know who the creatives were?

TM: Tim Yohannan (Aug. 15, 1945 – Apr. 3, 1998) was the founder of Maximum Rocknroll. Yohannan, also known as Tim Yo, was a 1960s counterculture leftist, before shifting this ideology to the punk scene.

SPD: How does that inform your creative now?

TM: I don’t really get a chance to use the raw visual design aesthetic of ’80s punk and hardcore anymore. (That would be so cool!) But I still feel strongly grounded in the DIY approach to design. In that sense, I like to think of a magazine as a group of friends who are dedicated to an idealistic cause and use their limited resources to make something fresh, beautiful, exciting and true to life. I see the punk scene and Maximum Rocknroll as that same arrangement. Deep down I am still as committed as ever to this way of thinking. I like to do things by hand, and I like stuff that is kind of beat up and messy. I like things that are directly expressive and unpretentious. I like starkness. I’m still an idealist. I’m still a punk rocker at heart—even though I let my mohawk grow out years ago!